Density and Intimacy in Public Space.

A case study of Jimbocho, Tokyo's book town

This piece was originally published in the Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health.

Abstract

Micro-scale and macro-scale hold opposite positions. Micro-scale holds a comparatively “private position” of isolation and protection; a feeling of “being away from prying eyes”, similar to a nest shaped by body’s weight. Macro-scale is more “chaotic”, disorderly saturated and entangled. The personal sphere, if projected to the present day metropolis, needs appropriate spatial conditions that allow intimacy and density to co-exist.

Within these spatial conditions, density and intimacy are not in opposition but are more like a designing synthesis. There, a positive or negative response will not be relevant because it would be more interesting to study and analyze their levels of implementation related to their surroundings.

Density and Intimacy in Tokyo Public Space identifies the Jimbocho neighborhood of Tokyo as a pragmatic case study through which its urban design becomes a conjunctive component between body and city, individuality and commonality; an area where public places protect the intimacy of mental wellness, even within Tokyo’s metropolitan density. Urban design becomes for this paper the perfect vehicle to conciliate these two realities - density and intimacy - in a soft and responsive way. It tries to answer the following questions: which are the spatial configurations allowing corporal micro-scale to coexist together with urban macro-scale? How to relate intimacy and density within public space?

Introduction

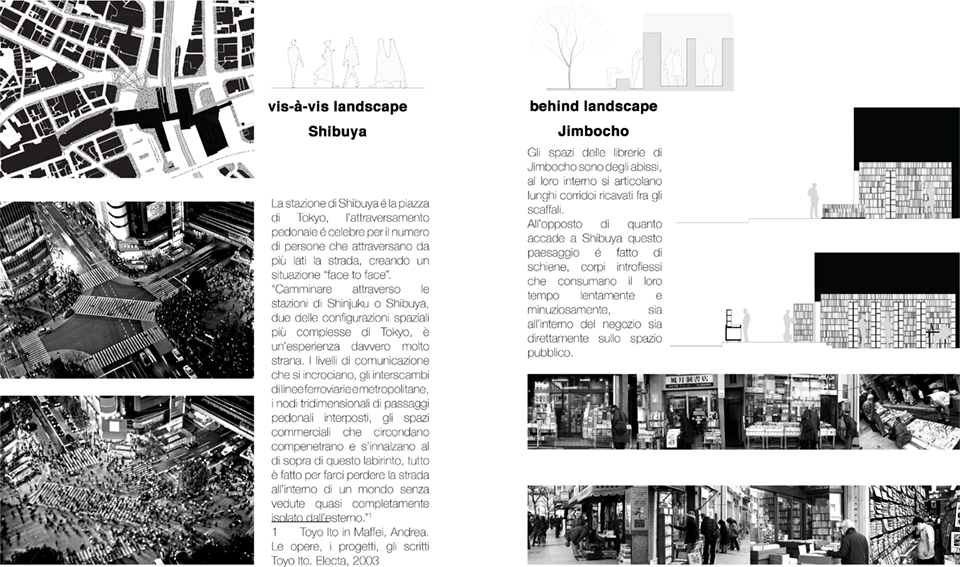

Tokyo is one of the biggest urban centers in the world, a place of major density that reaches its peak with its infrastructural hub Shinjuku, where 3.64 million people cross each other’s paths every day, making it one of the most crowded train station in the world. Shinjuku moves people into the city through its 65 exits that create a hybrid combination of architectural limits, together with infrastructural and urban limits. Shinjuku represents a cross-functional system in which there is a combination of eclectic players: shopping malls, stations, stores, and both public and private places that develop in a surprising and heterogeneous multi-layered shape.

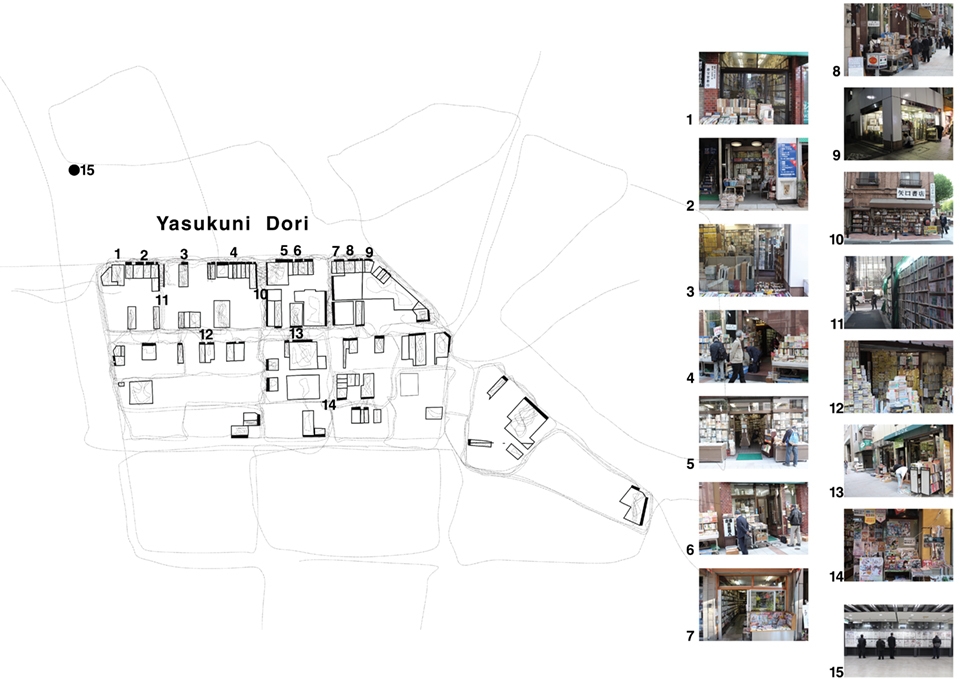

From this massive density originates the major thoroughfare of Yasukuni Dori, extending eastwards out of Tokyo and into Chiba, one of the most populated residential suburban areas that widens past the Sumida River. Along this road, shops, restaurants, financial and trade centers run across Tokyo for more than 10km. Not far from Shinjuku railway hub’s density and situated along Yasukuni Dori is the “juxtaposing” Jimbocho 神保町 aka the “books neighborhood” or “Tokyo's book town”.

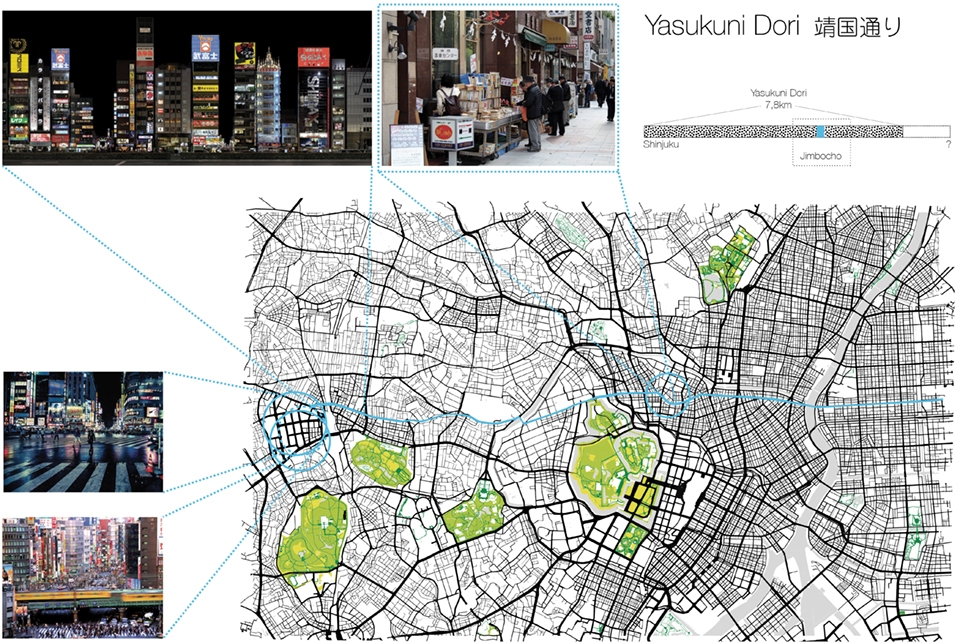

Figure 1: The road Yasukuni Dori begins in Shinjuku and extends eastwards through Tokyo and into Chiba (red line), Alice Covatta, 2017

Bookshops were built in this area because of important publishing houses and the proximity of a cluster of universities (Meiji University, Hosei University, Tokyo Gakuen University, Nihon University, Senshu University, Kyouritsu Women’s University, Juntendo University, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, and Chuo University). In the 1920s many college students, Japanese scholars and thinkers hung out in Jimbocho. Many of them shared the same liberal and progressive theories that disapproved of the growing nationalist extremism that reached its peak during World War II. Today Jimbocho resembles a human landscape made of backs facing walls that are fully covered by books, posters, manga and anime. These images cover the neighborhood’s vertical and horizontal surfaces, extending towards sidewalks and city walls.

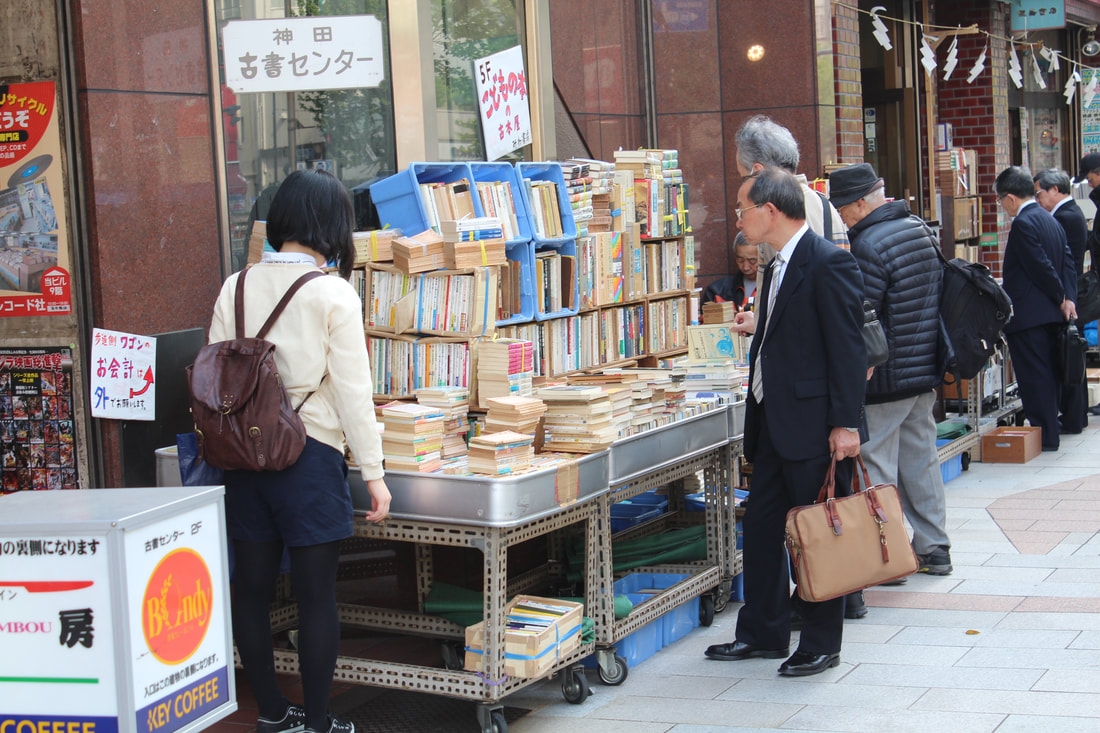

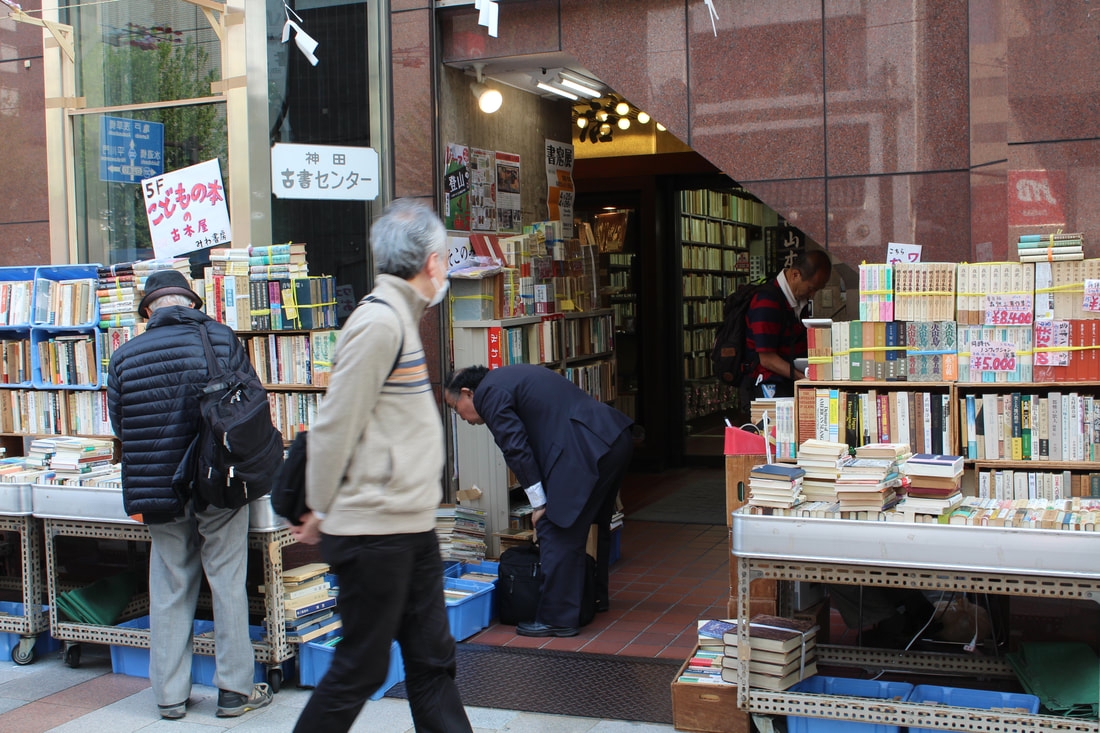

Figure 2 and 3: Visitors browsing at outer extensions and entering Jimbocho's bookshops, Alice Covatta, 2017

Jimbocho is a tactile landscape, a real “melting-pot” inclusive of eccentric characters wearing thick glasses, college students, workaholic managers and curious tourists. For more than a century, Jimbocho’s longevity and peculiarity have made it a magical place for native Tokyo citizens. Even a quick glance at this neighborhood immediately reveals its anachronistic features, emphasized by its clear differences with its surroundings. This secondhand book-shopping district covers an area of about 600m, where 168 bookshops occupy 4 hectares of one of the most overcrowded part of the Japanese capital. When in Jimbocho, visitors cannot fail to notice its peculiar type of “urban fabric” where almost every bookshop creates an outer extension and transforms the streets into a permanent marketplace. This outer extension creates a one-of-a-kind overturning because readers have an intimate feeling right in the middle of a traffic-congested arterial road. The described uncanny environment has developed behaviors, movements, traditions and rituality typical of this area, where one can openly see the leisure time of Jimbocho’s visitors .

In the Jimbocho neighborhood, the hectic and linear movements typical for an overcrowded arterial road like Yasukuni Dori are interwoven with the micro-movements of its users who hesitantly enter its bookshops. The subjective, inward/outward, erratic and volatile movements mark a clear break in the area where this book town is located. Within this framework, this paper highlights how Jimbocho has been developed around the intimacy of reading and seeks to underline the urban elements favoring its particular status and behavior.

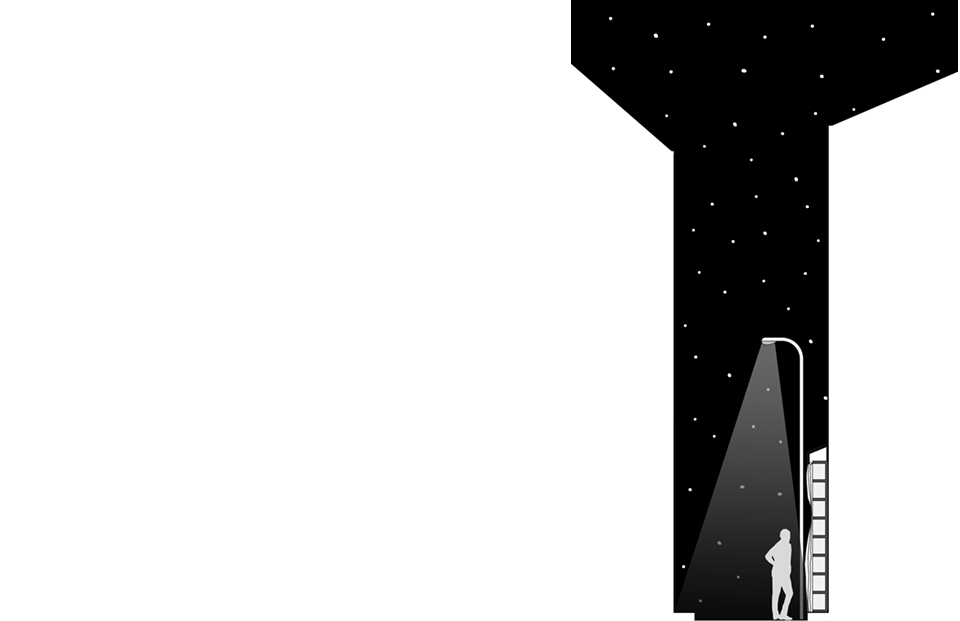

Figure 4: Street section, Alice Covatta, 2017

A neighbourhood characterised by bookshops was chosen for this study because reading is a typical human behavior which has been linked to psychological and physical wellness (Wilson et al, 2013, Billington et al, 2010). Studying the appropriate urban environment to favor reading behavior becomes a fundamental factor in understanding particular ways in which the environment can contribute to mental wellness now and in the future.

From an historical perspective, reading started to be considered as therapeutic tool since the beginning of the 20th century when the American Library Association started the first planned integration between books and medical professions by promoting libraries in hospitals and other therapeutic centers. The word bibliotherapy appeared for the first time in the 1930s, coined by Karl and William Menninger. The two psychiatrists used the practice of bibliotherapy in their Menninger Clinic in the US where they 'promoted the use of books for patients with mild neuroses or alcohol problems, or as support for relatives of patients and for parents of children' (Pehrsson and McMillen, 2005).

Considering the book as powerful tool for human wellness, this paper aims to highlight a possible design correlation between space for reading and mental health through the unique bookscape of Jimbocho and the subculture that it produces. During the investigation three different scales were considered - the small human scale of the body, the medium scale of the street and the larger scale of the city - that multiscalar approach aims to show the echo of words on paper reaching the scale of the biggest metropolis in the world.

Methods

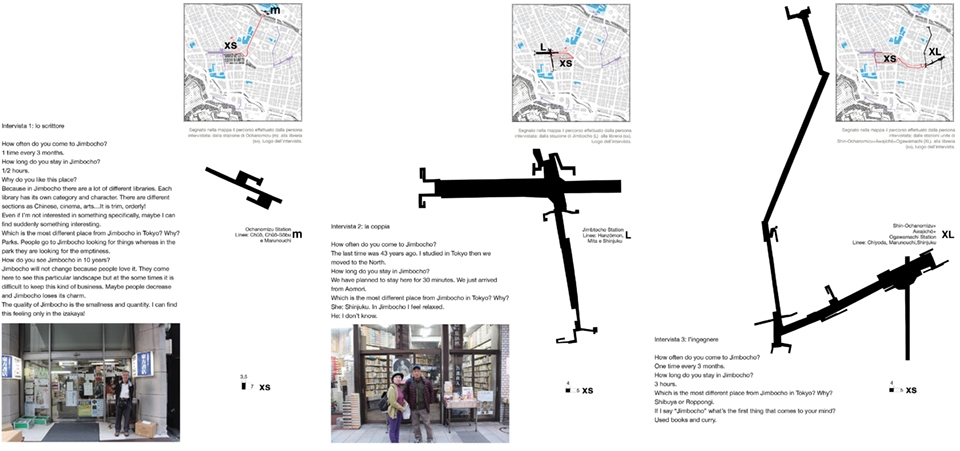

Two different research methods were used. The first was observation of behaviors of both visitors and of architectural and urban elements that give people shelter and hospitality. The second was interviews with a selection of Jimbocho’s visitors in order to understand their genuine perceptions of the area. Questions were asked to those who hang out at the outer reach of bookshops towards Yasukuni Dori and focus on the perceptual quality that individual subjects experience in that particular place and time, within their sphere of intimacy and reading.

Figure 5: Interviews with people visiting Jimbocho, Alice Covatta, 2017

The interviews took place during three consecutive weekdays afternoons. This time was chosen because Jimbocho generally reaches its peak of daily visitors at that time, encountering people who tend to pop into the shops during an ordinary working day while simultaneously the city around flows at maximum speed.

Nine people were interviewed. All were Japanese, but selected for their diverse backgrounds: one retired married couple visiting from the North of Japan, one older man who authored a book about Tokyo's manholes, one young student couple, one middle-aged systems engineer, one sculptor looking for arts book and two office workers from a nearby company. All questions were asked in Japanese to enable interviewees to feel more comfortable in expressing their opinions.

The following questions were asked of all interviewees:

▶Personal details

▶How many times do you come to Jimbocho?

▶How long do you usually stay in Jimbocho?

▶Describe your movement inside the neighborhood and station, and your personal itinerary? (Draw on a map)

▶Why do you like Jimbocho?

▶What is the most different place from Jimbocho in Tokyo? Why?

▶How do you see Jimbocho in 10 years?

▶If I say 'Jimbocho' what is the first thing that comes into your mind?

Results

The findings of this case study, starting from the analysis of Jimbocho, become planning and operative actions for future scenarios promoting the intimacy of human sphere within metropolitan density. An alternation of urban elements and recorded behaviors, none of which can exist without the other, composes the final list. Urban design becomes the perfect tool for communication between urban elements and recorded behaviors; it also welcomes inside public spaces one of the most intimate and solitary behavior of human beings: reading.

Design for intimacy in reading: lodge, minimal space and mobile items

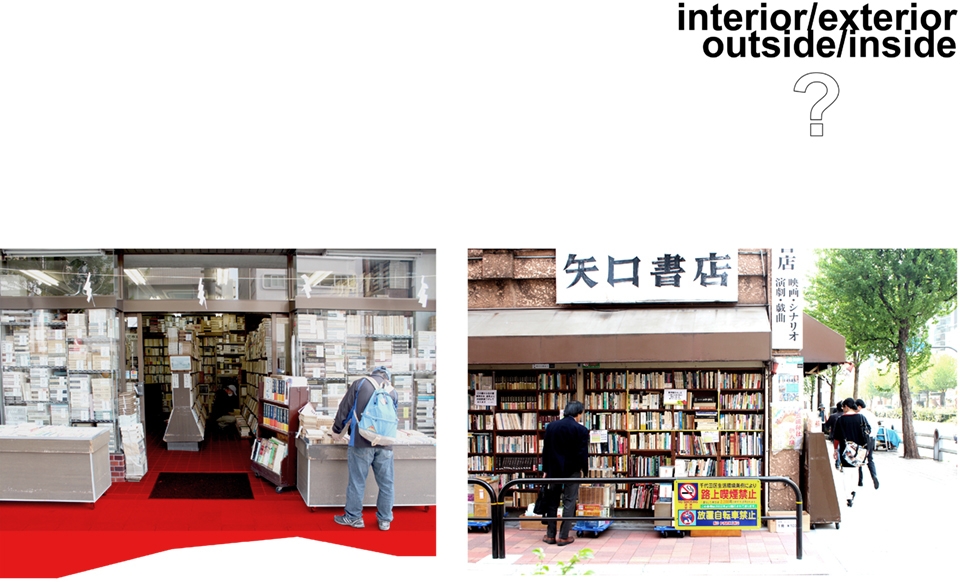

Bookshops’ borderline condition in between outside and inside has favored some unique typological solutions that can better relate when connecting to public spaces.

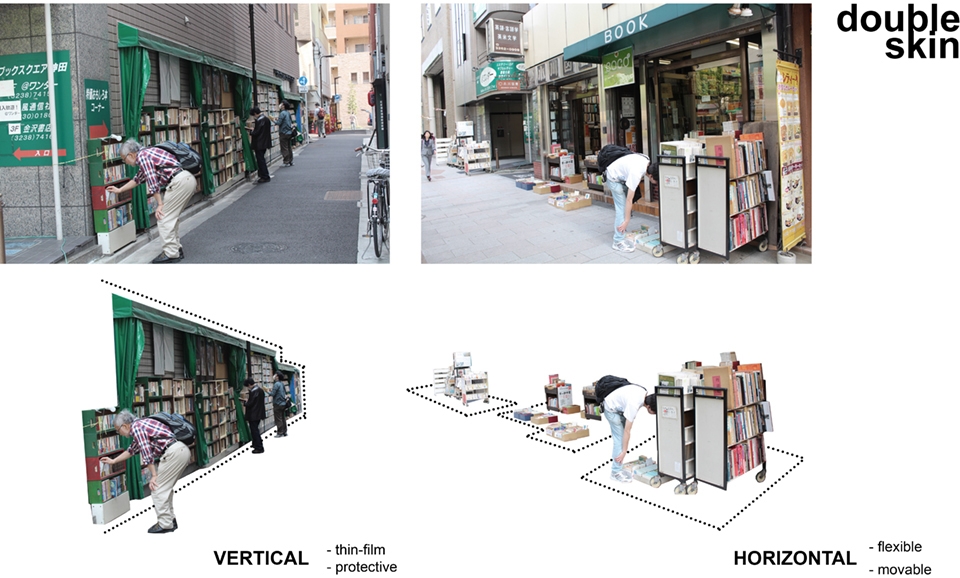

Since most of the shops are built directly on the street to display their goods for business purposes, a “lodge” is the most used architectural element. A lodge plays the hybrid role of “double-function space”: it bends over intimacy as a climatic shelter and, at the same time, it overlooks toward the city as an exhibition gallery.

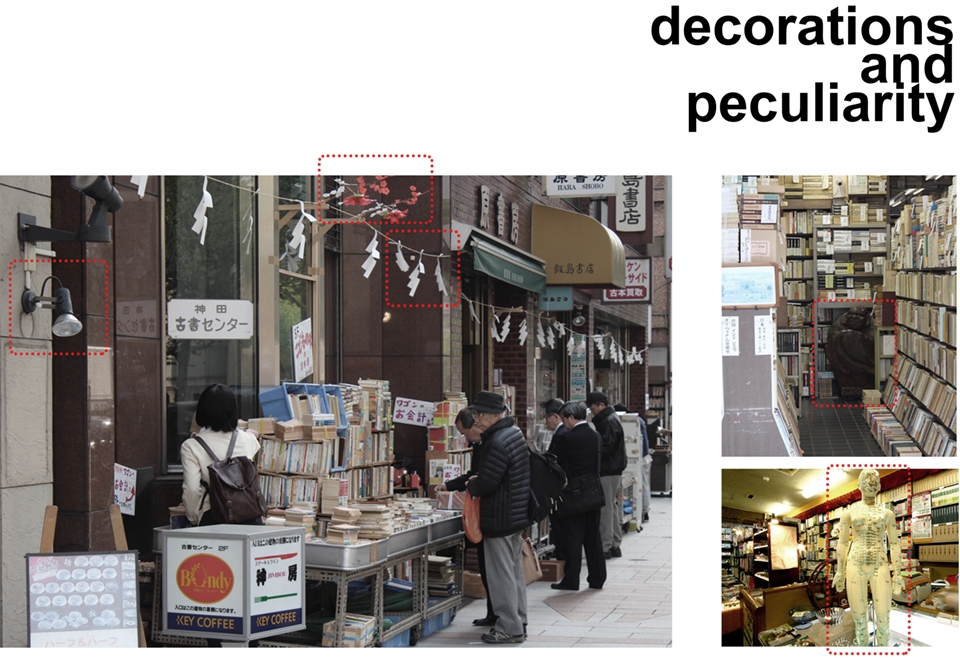

Figure 6: Inside or outside?, Alice Covatta, 2017

A lodge is both individual and universal, both private and public. Its small size helps deliver major individuality that absorbs the rapid flow of big cities, minimizing the distance between body and architecture. The exhibition elements located underneath the lodge are flexible and movable and they are set up according to the reader’s needs: below the lodge, three to four people can check and find books first outside and then move inside the bookshop if they need any more information. Every business has a unique essence and taste, celebrated through decorations, relics or peculiarities disclosed in the inside and outside of the shop. The lodge with its tiny dimensions and the presence of movable elements and oddities multiplies the possibilities of interaction between the city itself and its inhabitants beyond what would have happened with a dull surface clearly defined in its edges.

Figure 7: Double skin, Alice Covatta, 2017

Programs

By optimizing available spaces, the architecture has been shaped around readers’ needs. In this way, many bookshops target a specific topic like Chinese Art, movies, medicine, manga, computer science, posters, vintage toys and so on. An interviewed man describes this systematic organization of the area, with its many shops dedicated to specific items, as one of the most attractive feature of Jimbocho. He believes that this organization helps Jimbocho’s visitors to create an individual path tailor-made to their specific needs and desires. This same man proposed that the antithesis of this organized ‘book town’ is the park: a place he goes to meet his need for an endless emptiness.

Figure 8: Peculiarity, Alice Covatta, 2017

Jimbocho has a limited surface but simultaneously it offers a wide range of programs condensed together. This inconsistency is very similar to the idea of “master program” where a temporal aspect is involved rather than a “master plan”. Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki in his book Investigation in collective form describes the difference between “master plan” and “master program” in this way: “Our concern is not, then, a “master plan” but a “master program” since the latter term includes a time dimension. Given a set of goals, the “master program” suggests several alternatives for achieving them, the use of one or another of which is decided by the passage of time and its effect on the ordering concept” (Maki, 2004).

Food, reading, food

The large number of book shop visitors has encouraged many complementary businesses to flourish, creating several business opportunities in the area beside bookselling. The bookshops invite visitors to engage in inevitable behaviors such as reading while standing, isolation, obsessive research, checking and sifting, and wandering about, behaviors inclusive of any nationality or social class. These behaviors are the main reason why Jimbocho has so many business units with specifically designed and equipped areas where one can comfortably sit, read a book, have a coffee or a cup of green tea.

Bibliophilia manifests itself both in small coffee bars and in big retail corporations alike. In Jimbocho, the large chain coffeeshop Doutor has personalized its corny interior design to have what is necessary to make the reader feel comfortable and at the right place: isolated with an armchair next to a small table and an appropriate lamp in a silent corner. Even consumerism, based on the standardization of behaviors, adapts itself to Jimbocho’s rules.

Figure 9: Size, Alice Covatta, 2017

Other behavior that is well suited to reading, and in general to Tokyo’s lifestyle, is eating fast. There are many fast-food restaurants in Jimbocho selling curry-based meals. Curry is always served with rice and it may be the only dish in Japanese cuisine that does not require chopsticks: readers can hold a book in one hand while easily, with the other hand, eating rice and curry with a spoon without the need to look at the dish and divert focus from what they are reading.

These small observations can be seen as futile, but they actually reveal a lot about how this area has been shaped around its users’ reading behavior. This virtuous cycle made of architectural, economical and socio-cultural factors is a wonderful alchemy of perfect balance between architecture – city – inhabitants.

Psycho-geographic map

Figure 9: Movements, Alice Covatta, 2017

People arriving at Jimbocho have a specific psycho-geographic map that touches various places of interest typical of this neighborhood. Interviewees revealed that they accurately plan/schedule their visit to specific bookshops and they follow pre-defined itineraries. During one interview, a computer engineer claimed to come once every two weeks, a sculptor at least once a week; and an employee of a multinational company located in the same area, at least once a day, preferably during lunch break. Only an elderly couple contradicted the regularity with which the other respondents visited: they had come to Jimbocho from Northern Japan to celebrate their 40th wedding anniversary to revisit those streets after 35 years.

Belongingness/Community

Jimbocho's history is pretty long in comparison with Tokyo lifespan and for over a century the book district has produced a unique subculture in the city. It is not to be considered as a mere consumeristic act but instead it is affection to the neighborhood, to the trust relationship among customer and bookseller, to the subculture of book lovers.

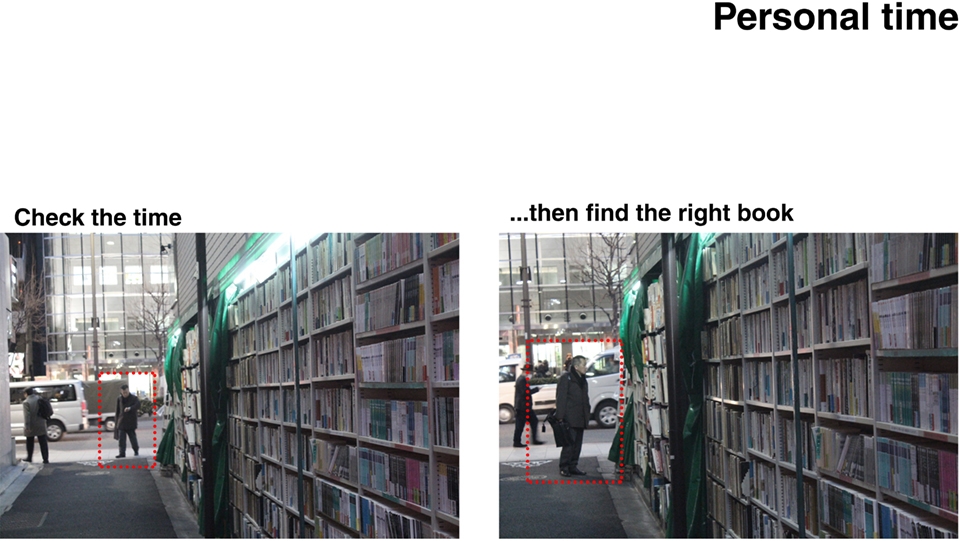

Figure 10: Personal time, Alice Covatta, 2017

From the interview, the time spent in Jimbocho, both as part of an everyday schedule and for special occasions, creates a heterogeneous community of people belonging to different social status and background but in Jimbocho they all belong to the same community. The book district erases social differences and helps creates a democratic city: even if they are strangers these people all share together the same passion for reading and books.

Discussion

Haruki Murakami writes:

“I go back to the reading room, where I sink down in the sofa and into the world of The Arabian Nights. Slowly, like a movie fadeout, the real world evaporates. I'm alone, inside the world of the story. My favorite feeling in the world”.

In Jimbocho this feeling takes place in the city’s public area, allowing those personal gestures related to reading to be publically exposed. Reading becomes the element transforming urban space, showing the intimate human time in opposition to the city movement around.

Jimbocho proposes a self-sufficient, self-regulating system in urban density. The observation of behaviors and of architectural elements that underline that Jimbocho neighborhood can be characterized by the following features:

Its peculiar shops' typology

Its complementary programs that take place in the area

Its status of being the main cause of a reverberation in public spaces

Its interpenetration between individual units and architecture

Its visual culture

Its users’ undeniable affection for the community

At last, what emerges from interviews and observation of behaviors is that repetition of personal rites, such as reading, creates affection to the space, contributing to mental wellbeing. Dead time, slowness, boredom, Jimbocho's imperceptible variations belong to personal time and they increase when opposed to the speed and loudness of a huge city spreading out only few meters away. The actors who work there and the readers share the intimacy of reading in the city's collective space, forming a heterogeneous community that nullify social inequalities and at the same time, “...make them feel alone, within the world of the story. My favorite feeling in the world”.

Figure 11: Shibuya vs Jimbocho, Alice Covatta, 2017

References

Billington J, Dowrick C, Hamer A, Robinson J, Williams C (2010). An Investigation of the therapeutic benefits of reading in relation to depression and wellbeing. University of Liverpool.

Boontharm, D., & Radović, D. (2012). Small Tokyo. Tokyo: Flick Studio.

Bruno, G. (2007). Public intimacy: Architecture and the visual arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gehl, J., & Rogers, L. R. (2013). Cities for People. Washington DC: Island Press.

Juhani, P. (2014). The eyes of the skin: Architecture and the senses. Chichester: Wiley.

Kaijima, M., Kuroda, J., & Tsukamoto, Y. (2006). Made in Tokyo: Guide book. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Pub.

Maki, F. (2004). Investigations in collective form. St. Louis: School of Architecture, Washington University.

Nakamura, H. (2010). Microscopic designing methodology. Tokyo: Inax Publishing.

Perec, G., & Sturrock, J. (2008). Species of spaces and other pieces:. London: Penguin.

Pehrsson, D., McMillen, P. S. (2005). A Bibliotherapy evaluation tool: Grounding counselors in the therapeutic use of literature.The arts in Psychotherapy, 32(1), 47-59.

Qiu, X. (2013). Fumihiko Maki and his theory of collective form: A study on its practical and pedagogical implications.

Suzuki, A., & Terada, M. (2006). Archilab Japon Orléans 2006 faire son nid dans la ville. Orléans: Éditions HYX.

Tsukamoto, Y., & Kaijima, M. (2010). Behaviorology. New York: Rizzoli.

Tsukamoto, Y., & Bow-Wow, A. (2015). Windowscape. S.l.: S.n.

Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Barnes LL, Schneider JA and Bennett DA. Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology July 23, 2013 vol. 81 no. 4 314-321